About Harriet Tubman

The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway recounts the life story of Harriet Tubman – freedom seeker, Underground Railroad conductor, abolitionist, suffragist, human rights activist, and one of Maryland’s most famous daughters. Born around 1822 in Dorchester County on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, Tubman is one of the most lauded, recognized, and revered figures in American history.

Her life and legacy will be shared even more widely if and when the new U.S. $20 bill is unveiled; a new design may feature her likeness. If so, then Harriet Tubman would become the first woman and first African American on U.S. paper currency.

A courageous leader

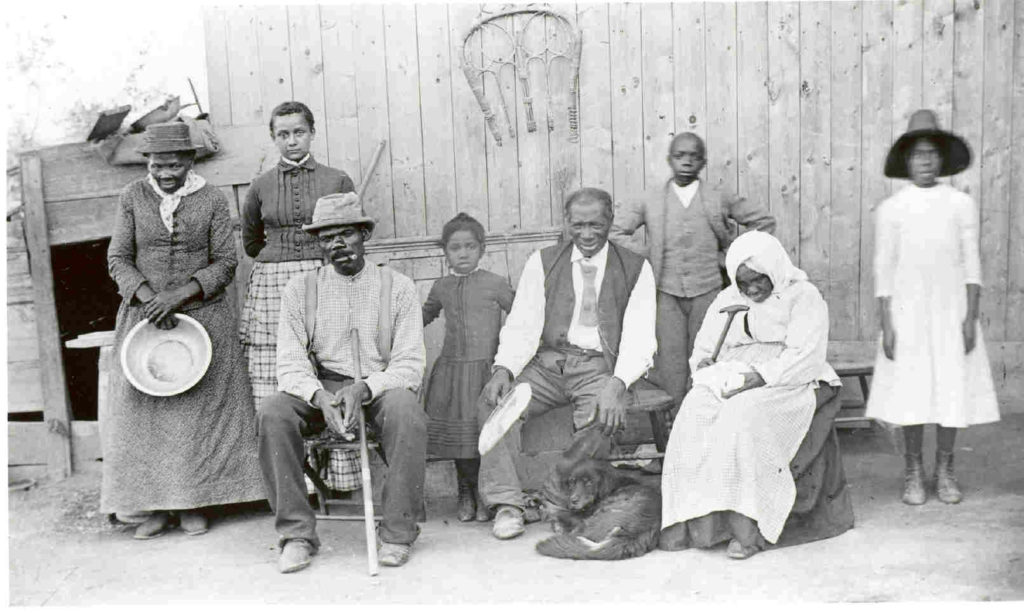

The middle child of nine enslaved siblings, Harriet Tubman was raised by parents who struggled against great odds to keep their family together. She overcame a severe disability, maturing into an expert hunter, lumberjack, and fieldworker. Her prowess prepared her for the dangerous path she’d pursue as an adult.

Tubman successfully escaped to Philadelphia in 1849. Once free, she became an operator of the Underground Railroad — a secret network of people, places and routes that provided shelter and assistance to escaping slaves. She courageously returned to Maryland at least 13 times over the course of a decade to rescue her parents, brothers, family members, and friends, guiding them safely to freedom. By 1860, Tubman had earned the nickname “Moses” for liberating so many enslaved people at great risk to her own life.

Did you know?

Facts About Harriet Tubman

- She never learned to read or write, but was smart, calculating, and bold—and was never caught during her 13 dangerous missions to lead her friends and family out of slavery.

- During the Civil War, she became the first woman to lead an armed military raid in June 1863. She was also a Union scout, spy, and nurse.

- She was a suffragist who fought for women’s rights.

- She established a nursing home for African Americans on her property in Auburn, NY.

- Tubman nearly died as a young girl after a traumatic head injury. The rest of her life she suffered from seizures, pain, and other health complications.

- She was devout. When she began experiencing visions and vivid dreams, she interpreted them as revelations from God.

A dedicated humanitarian

Deeply admired by abolitionists in the North, Tubman became a trusted friend and advisor to many, which earned her a role in the Union Army as a scout, spy, nurse and confidante of generals. After the Civil War, she moved to Auburn, NY, where she turned her attention to the plight of the needy, opening her home as a sanctuary for the elderly and ill and those with disabilities.

Even before the Civil War, she was fighting for the rights of women, minorities, disabled, and the aged. She became more active with time. She went on to open a nursing home for African Americans on her property in New York. She continued to agitate for women’s rights until her death in 1913. By then, Tubman had become the subject of numerous articles, recollections and an autobiography.

While cloaked in mythology for far too long, Tubman’s life is finally being viewed in proper proportion. One needs only to visit the Byway that bears her name to grasp the significance of her humble beginnings and scale of her achievements. Tubman’s role was to serve others, fight oppression and make a difference in the world — all ideals that are celebrated along the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway, where ordinary people did extraordinary things.

A brief timeline

- She was born Araminta “Minty” Ross into slavery in Dorchester County, Maryland, probably around 1822. Her parents, Harriet (“Rit”) Green and Ben Ross, were both enslaved.

- The Brodess family who “owned” her mother hired Harriet out and assigned her to do work including caring for children, checking muskrat traps, field and forest work, driving oxen, plowing, and hauling logs.

- She suffered a traumatic head injury as a young girl, probably in the 1830s. The injury caused a lifetime of seizures, headaches, and visions.

- After she married John Tubman, a free Black man, around 1844, she changed her name from Araminta to Harriet, and thus became Harriet Tubman.

- She escaped slavery and made it to Philadelphia, traveling alone mostly under the cover of night, in 1849.

- After she escaped, she spent more than 10 years making secret return trips to Maryland to help her friends and family escape slavery. With each trip she risked her life. Her last rescue mission was in 1860.

- When the Civil War began, Tubman worked for the Union Army, first as a cook and nurse, and then as an armed scout and spy. In 1863, she became the first woman to lead an armed expedition in the war, liberating more than 700 slaves.

- After the Civil War, she moved to property she had purchased in 1859 in Auburn, New York, where she cared for her aging parents.

- She was involved in the suffrage movement, fighting not only for the rights of women, but also for minorities, the disabled, and the aged.

- She died on March 10, 1913. She is buried in Auburn, New York.

- On April 20, 2016, the U.S. Treasury Department announced a plan for Tubman to replace Andrew Jackson as the portrait gracing the $20 bill.

Dispelling the myths about Harriet Tubman

“We think we know Harriet Tubman: former slave, Underground Railroad conductor and abolitionist. But much of Tubman’s real life story has been shrouded by generations of myths and fake lore, propagated through children’s books, that has only obscured her great achievements. The truth about the woman who will become the new face of the $20 bill is far more compelling and remarkable.”

— Kate Clifford Larson, author of Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman: Portrait of an American Hero,

Kate Clifford Larson, author of the respected biography of Harriet Tubman called Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman: Portrait of an American Hero, points out myths and facts about Harriet Tubman’s life. We include some of the myths here, with permission of the author.

FACT: According to Tubman’s own words, and extensive documentation on her rescue missions, we know that she rescued about 70 people – family and friends – during approximately 13 trips to Maryland. During public and private meetings during 1858 and 1859, Tubman repeatedly told people that she had rescued 50 to 60 people in 8 or 9 trips. This was before her very last mission, in December 1860, when she brought away 7 people. Sarah Bradford exaggerated the numbers in her 1868 biography. Bradford never said that Tubman gave her those numbers, but rather, Bradford estimated that was the number. Other friends who were close to Tubman specifically contradicted those numbers. We can name practically every person Tubman helped. In addition to the family and friends, Tubman also gave instruction to another 70 or so freedom seekers from the Eastern Shore who found their way to freedom on their own.

FACT: Jacob Jackson, a free Black farmer and veterinarian, was Harriet Tubman’s confidante. Tubman had a coded letter written for her in Philadelphia and sent to Jackson in December 1854, instructing him to tell her brothers that she was coming to rescue them and that they needed to be ready to “step aboard” the “Ol’ Ship of Zion.” There is no documentation that he actually sheltered runaways in his home. Jackson would be referred to as an agent.

FACT: Harriet Tubman never used the quilt code because the quilt code is a myth. Tubman used various methods and paths to escape slavery and to go back and rescue others. She relied on trustworthy people, Black and white, who hid her, told her which way to go, and told her who else she could trust. She used disguises; she walked, rode horses and wagons; sailed on boats; and rode on real trains. She used certain songs to indicate danger or safety. She used letters, written for her by someone else, to trusted individuals like Jacob Jackson, and she used direct communication with people. She bribed people. She followed rivers that snaked northward. She used the stars and other natural phenomenon to lead her north. She also trusted her instincts and faith in God to guide and comfort her during difficult and unfamiliar territory and times.

FACT: Tubman sang two songs while operating her rescue missions. Both are listed in Sarah Bradford’s biography Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman: “Go Down Moses” and “Bound For the Promised Land.” Tubman said she changed the tempo of the songs to indicate whether it was safe to come out or not. Follow the Drinking Gourd was first written and performed by the Weavers, a white folk group, in 1947, nearly 100 years after Tubman’s days on the Underground Railroad. “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” was written and composed after the Civil War by an Afro-Cherokee Indian living in Oklahoma and therefore would have been unknown to Tubman before the Civil War.

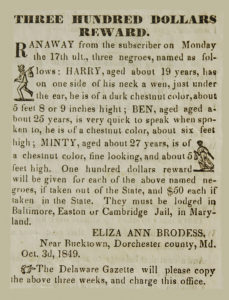

FACT: In fact, Tubman was a relatively young woman during the 11 years she worked as an Underground Railroad conductor. She escaped slavery, alone, in the fall of 1849, when she was 27 years old. A runaway advertisement at the time, offering $100 for her capture, described her as “of a chestnut color, fine looking, and about 5 feet high.”

Tubman is often portrayed in popular culture — in art, monuments, picture books and living-history presentations — as a decrepit old woman. This reflects photographs taken late in her life, which, as Washington Post critic Philip Kennicott noted, “have the effect of softening the broader memory of who she was, and how she accomplished her heroic legacy.”

Tubman Visitor Center

Learn Harriet Tubman’s Story at the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor Center

The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor Center opened to the public in March 2017 in Church Creek on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Harriet Tubman, who grew up in slavery in Dorchester County, lived, worked, and worshipped in places near the visitor center. It’s from this area that she first escaped slavery, and where she returned about 13 times over a decade, risking her life time and again to lead some 70 friends and family members to freedom. To carry out the dangerous missions, she used the Underground Railroad, a secret network of places and people.

Location: 4068 Golden Hill Rd., Church Creek, MD

Hours: For the latest information, click here.

Admission: Admission to the visitor center is free, but donations are welcome

For more info: Tubman Visitor Center website, 410-221-2290, or htursp.dnr@maryland.gov.

Located near Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge and about 25 minutes from Cambridge, Maryland, the beautiful visitor center includes an exhibit hall with powerful and thought-provoking multimedia exhibits, a theater, and gift shop. The visitor center is on the grounds of a 17-acre state park with short walking trails. There’s also a large picnic pavilion with a stone fireplace that’s available for rental. The visitor center is a joint operation between the Maryland Park Service and the National Park Service.

The visitor center is one of more than 30 sites of historical significance along the Maryland portion of the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway, a self-guided, scenic driving tour. Many of the exhibits include specific sites along the Tubman Byway where you can experience more of the stories.

NOTE: The Tubman Visitor Center is different than the Harriet Tubman Museum & Educational Center, which has been in existence for more than 20 years and is run by dedicated volunteers in downtown Cambridge. The museum’s founders helped keep Tubman’s legacy alive.

Find out more about the Tubman Visitor Center on the Tubman Visitor Center website, or contact them at 410-221-2290 or htursp.dnr@maryland.gov.

National Historical Park

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park

An executive order in March 2013 established Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument and marked the landscape of Dorchester County, Maryland for its historical significance to Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad. At the creation of Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park a year later, the National Park Service identified land in Dorchester, Talbot, and Caroline Counties for potential future acquisition. The Conservation Fund donated the only land currently owned by the National Park Service—480 acres at the Jacob Jackson site, the home of a free African American who delivered a message for Tubman that she was returning to guide her brothers to freedom.

The National Park Service also administers a sister park in Harriet Tubman National Historical Park in Auburn, New York, where Harriet Tubman lived in her later years.

Passport to your National Parks stamps are available at the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor Center.